Where Was God When Jesus Died?

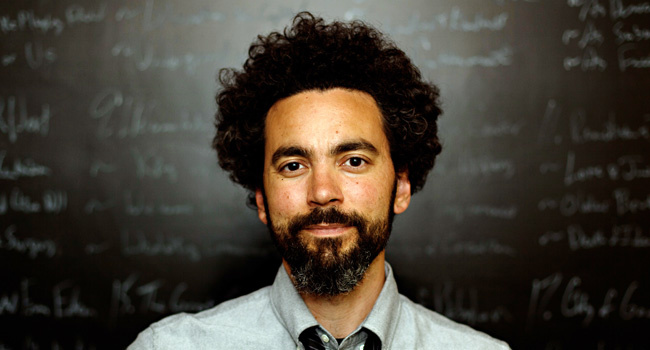

The following post was written by my excellent friend and killer author, Joshua Ryan Butler. This dude rocks like none other and his latest book, The Pursing God, is absolutely incredible. Here's an excerpt from it:

Where was God when Jesus died? Some have characterized the cross as divine child abuse—the Father beating the snot out of his Son—to critique the notion that God is actively present doing something at the cross. Others claim if God left the building, it’s neglect and abandonment. While both of these are caricatures, it’s worth asking:

“Was the Father absent or present during the death of his Son?”

Exile is a helpful lens, I would suggest, to look at this question through. Jesus understood his death as bearing Israel’s exile–and our exile, our distance from the presence of God–in his crucified humanity on that tree. And Israel understood exile as arising from both the absence of God (from one important angle) and the presence of God (from another).

Let’s see how this worked.

Exile as Absence

First, Israel saw her exile as the result of God’s absence. God pursued his people relentlessly throughout her history, but Israel repeatedly worshipped idols and unleashed injustice—becoming more and more corrupt. God sent prophets and messengers to call her back, but the people killed the prophets and rejected the messengers, preferring to live on their own.

Israel essentially asked God for a divorce; so finally, God left town.

Catching his wife in bed with another man one too many times, God packs his bags and vacates their home. In a famous passage, Ezekiel sees God’s glory departing the temple, the place where God dwelt most intimately with his people. With suitcase in hand, God walks out of the “bedroom,” exits the temple courts, and leaves the building. It’s as if God is saying,

“I’m tired of her cheatin’ ways. She wants her other lovers; she can have ’em. I’ll take up shop in a heavenly hotel, and she can sleep around down here with whoever she wants.”

The unrequited Lover gives his wayward wife the separation she craves. This is the climax of Ezekiel’s prophecy.

God’s glory departs the temple.

Without God’s protective presence, Babylon invades. God’s presence was what kept her safe from invasion in the first place. God was her Defender from the mighty empires that surrounded her. Now, with her husband away, the cruel lovers pounce. With the King gone, Babylon swoops in to seize his kingdom: the pagan empire destroys the temple, sets fire to Jerusalem, lays waste to the land, and takes the people into captivity in a land far, far away.

Israel is given her lovers, handed over to what she’s chosen.

Exile arises from God’s absence.

Exile as Presence

And yet, from another angle, God is also present. In a sweeping turn of phrase, God calls Babylon his “sword,” her king “my servant,” her armies his armies “to bring disaster on the city that bears my Name.” (Jer 25:9, 29; 43:10; Ez 21)

What?! This is crazy. How is God present in the godless, brutal butchers desecrating his holy home?

God declares he is at work in this event: chastising his people, driving them from the land, giving them over to what they’ve chosen, in hopes that the experience of destruction downstream will shake them to their senses and drive them back to the life they were made for—with him.

So Israel saw Babylon as God’s “iron yoke” and “cup of wrath,” doling out the paycheck her injustice and rebellion had earned. (Jer 25, 28-29, Ez 39:28). “I am raising up the Babylonians,” God says, “that ruthless and impetuous people.” The prophet Habakkuk responds, “You, Lord, have appointed them to execute judgment; you, my Rock, have ordained them to punish.” (Hbk 1:6, 12)

Second Chronicles recounts this logic of exile:

“The God of their ancestors, sent word to them through his messengers again and again, because he had pity on his people and on his dwelling place. But they mocked God’s messengers, despised his words and scoffed at his prophets until the wrath of the Lord was aroused against his people and there was no remedy. He brought up against them the king of the Babylonians.” (2 Chr 36:15-17; emphasis added)

The Babylonian captivity is the sovereign judgment of God.

Throughout the prophets, God repeatedly says he is the One sending them into exile, driving them out of the land, carrying them away, scattering them, and giving them over to the destruction they’ve chosen. God is actively involved in his people’s removal from the land.

The prophets reveal that when God seems to have left the building, he may be most powerfully at work.

Here’s the thing to recognize, however: though God and Babylon are both involved in the same event, their motives are starkly different—even diametrically opposed. The mighty empire simply wants to tear Israel down, while God ultimately wants to lift her up. The pagan power strives to distance the people from God; God’s endgame is to draw them to him.

It’s as if God and Babylon are driving together through Phoenix, but God’s final destination is to get to Los Angeles, whereas Babylon’s simply aiming for Death Valley.

The same event is oriented toward two very different goals. And God is ultimately in the driver’s seat.

Exile arises from God’s presence.

Forsaken and Indwelt

As Jesus bears Israel’s exile–and our exile, our distance from the presence of God–in his rejection, crucifixion, and death, this same imagery is at play. On the one hand, the cross arises from the absence of God. At the climax of Jesus’ crucifixion, he cries out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mt 27:46; cf. Ps 22:1) God’s protective presence has left the building, the Father’s glory has departed the temple of Jesus’ body, and his Son is now vulnerable as the pagan powers invade to tear down this Most Holy Place, to desecrate the sanctuary of his flesh and bone, to demolish him to rubble and carry him down to captivity in the grave.

Jesus is forsaken, the temple of his body destroyed.

The cross arises from God’s absence.

And yet, from another angle, God is present in the crucifixion. When Jesus cries out, he cries out to My God! And you don’t cry out to someone who isn’t there. More so, Jesus’ final words are of trust: “Father, into your hands I commit my spirit.” (Lk 23:46) As Jesus breathes his last, he entrusts himself to his Father and looks to him for vindication on the other side of the grave.

As we murder God’s Son, the Father’s arms receive the tattered, lifeless body of his beloved child.

God is present at the cross.

Here’s what’s crazy, however: God is doing something through this event. The Father is present not only over his Son, but in his Son. At Golgotha, Paul declares, “God was in Christ reconciling the world to Himself.” (2 Cor 5:19; emphasis added) In Jesus’ darkest hour, the Father is actively present accomplishing something—the reconciliation of the world. Colossians declares in a similar vein:

“God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in [Jesus], and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.” (Col 1:19-20)

God is dwelling in Jesus, working through Jesus, actively present at the cross—and his endgame is reconciling the world.

As with Israel’s exile, however, God’s motives are radically different from ours: we are out to crush the Son, while the Father is bearing our destruction in him to exalt him as Savior of the world. We kill Jesus to tear him down while God is at work uniting us to him as our new head, tearing our corrupted body down in him to ultimately build us up and lift us up through him.

We are striving to keep our world distant from God, while God is—in the very same event!—drawing our world most intimately close to him. As Jesus bears our distance from the presence of God upon himself (in his humanity), he simultaneously bears the presence of God within himself (in his divinity) into our distance. The Father is present through his Son and in his Spirit at the cross, working to bring us home.

Adapted from Chapter 15 of The Pursuing God: A Reckless, Irrational, Obsessed Love That’s Dying To Bring Us Home (Thomas Nelson: May, 2016).